Gaps – For more detailed chart analysis

The value of gaps: The best indicator of where price is likely to go (near-term) is the price chart itself. However, there are hundreds of indicators created to help solve this problem. Yet, all we have to work with on charts is:

Price (Open, High, Low, Close)

Volume

Time

All indicators are derived from these three factors and their many combinations. The goal is to see into the future, to determine where the price will go! Forget it… We can never know with certainty where the price will go. We can improve the odds, increase the likelihood of our “guess-success,” and that can provide the “edge” needed for success in the market. Proper use of indicators can be very rewarding.

The price chart can send subtle messages and indicators can help understand those messages. But, of paramount importance:

Most price charts tell us nothing most of the time!

We’ve introduced four type price gaps, Common, Breakaway, Runaway (or Measuring), and Exhaustion gaps. We covered common gaps in our last chat, showing them to be just that, “common,” with little trading significance. The next chart was a possible pick that didn’t make the cut this week which reinforces our last chat. Count the gaps and check to see if they were filled:

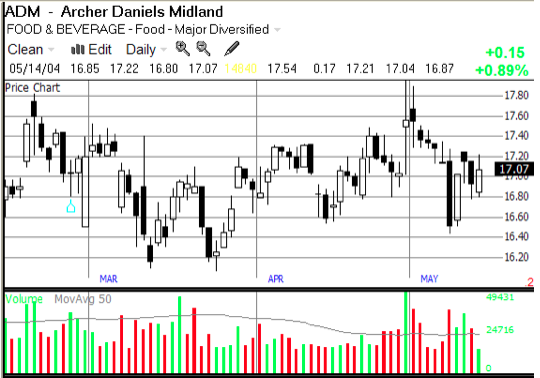

Fig. 1. Gaps on price chart.

I count four gaps, all filled. Gaps do tend to be filled, often magically, or so it seems. However, as we pointed out in the last chat, there is no law dictating that this must occur. It is usually because most prices trade in ranges and as such, the gap is filled naturally. Such is the case in Fig. 1 for ADM.

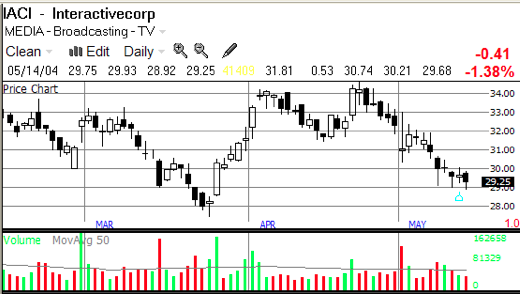

An exception occurs when a gap is not filled, as we’ll discuss in this chat, with the second type “breakaway” gaps. For example, look at the next chart, IACI, paying close attention to the volume level where the breakout occurred. How would we know if a gap is a breakaway or common? We have the luxury of hind-sight in his example, but true breakaway gaps are accompanied by a larger than usual daily volume. Breakaway gaps are often trade-able, that is, when other indicators are in place, this is a good entry point. Breakaway gaps do not need to be filled! In the following chart, given enough time, the price may fall to close the gap, but that is due to the trading range nearly two months later.

Fig. 2. An un-filled “Breakaway” gap.

Here is another example of a breakaway gap in MNST:

Fig. 3. A second “Breakaway” gap.

Breakaway gaps occur near the breakout of important consolidation patterns. This is notable because it separates the consolidation (a stalemate area) from the often violent breakaway. This type gap can occur in either direction, up or down. Upside breakaway gaps occur on increased volume; whereas downside breakaway gaps do not need heavy volume. If volume is not higher with the gap than before, odds are about even that the gap will be filled on the next few bars. If volume is higher, chances are slim that near-term action will fill the gap.

Let’s try to understand what goes on behind the curtain with a breakaway gap: Suppose a stock traded up to $18 per share, stopped, and then turned lower repeatedly. That is the congestion. That means there is both a persistent demand for and a large supply of stock available for sale at $18. Now, current holders of the stock see this price action and figure that once the stock breaks $18, it will go much higher. (Therefore, they hold their stock for a time.) This creates a vacuum; once the supply of $18 stock is gone, the next buyer finds none available at $18 and must bid higher, creating the breakaway gap. This is shown in the next two charts.

Fig. 4. A November breakaway gap on Xerox.

Fig. 5. A breakaway gap moving out of congestion.

In this breakaway example on HIBB, the move away from the congestion is not so obvious, but goes on to peak at $26 the 2nd of April before changing character. Notice also how volume increases to support the new trend.

Look at a weekly chart below for Fig. 1 on ADM. There is but one gap shown near the middle of the price pattern. This shows a 16-month time span with a single gap. This is a very important point: Gaps are more frequent on daily charts than on weekly charts. Why? There are simply more opportunities with daily than weekly. In the 16 month time span shown on the chart below, there are 64 weekly bars, which would include 320 daily price bars. A price gap on a daily pattern is easily gobbled up when the weekly action is shown. But here’s the point: Price gaps on weekly charts are much more significant than daily gaps! Because they are rare, they are more significant.

Fig. 6. Gap on price weekly chart.

Here is another important point. Almost every legitimate breakout from congestion is done on a breakaway gap. However, we will not always see them on a daily chart since they occur during the day and not between one day’s close and the following day’s open. This is similar to the occurrence of monthly gaps compared to the daily. But the fact remains, successful breakouts are accompanied by gaps. In another way, gaps rarely occur in false breakouts (those which fail to follow through in the direction of the breakout).

While looking at Fig. 6 we can make a final point about the third type gap, a “Runaway.” These are sometimes called “continuation” or “measuring” gaps. The runaway gap is a reliable indicator of a strong underlying trend as evident in Fig. 6. These gaps occur in the middle of fast up or down price movements and typically occur on moderate volume when the price seems to move effortlessly. These can occur with relatively high volume, increasing the probability of a strong underlying trend in the direction of the move.

Runaway gaps often occur about half-way through an up or down price move, as with ADM above. Therefore, you can expect that prices will move about the same percentage amount from the gap to the end as it has from the beginning to the gap. This will vary somewhat depending on whether the chart is log scaled or arithmetic.

Runaway gaps occur less often than common or breakaway gaps but are technically more significant. They are a sign of significant strength in an uptrend or weakness in a downtrend and are easy to distinguish from common or breakaway gaps. Runaway gaps are typically not filled until a considerable time has passed. In our next chat we will consider the last gap type, the “Exhaustion” gap. At that time we will talk about the similarities and differences between the runaway and exhaustion. Occasionally, more than one runaway gap can occur in a trend. When that occurs, the measuring feature is not so clear. Remember, each additional runaway gap brings the price top (or bottom) closer.

Learn with our products

SiteMap